The designation responds to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s call for commemoration

The federal government is formally recognizing one of the darkest chapters in Canadian history as an event of national significance and is designating two former residential schools as national historic sites.

Minister of Environment and Climate Change Jonathan Wilkinson, who is responsible for Parks Canada, officially announced today how the federal government is marking the history of the residential school system.

“From this day forward, the residential school system will be designated as an event of national historic significance, which will help to educate all Canadians on the system and its consequences and ensure that this part of our history is never forgotten or repeated,” Wilkinson said.

Wilkinson also announced two former residential schools are being designated as national historic sites: Portage La Prairie Residential School in Manitoba and Shubenacadie Residential School in Nova Scotia.

Dorene Bernard, a Mi’kmaq from Sipekne’katik First Nation and a survivor of the residential school system, has waited a long time for this moment.

Her grandmother, mother, father and siblings all went to the Shubenacadie Residential School. Bernard started attending in 1961 at the age of 4.

Too young for the classroom during her first year there, she said, she watched the older students lining up for class and being hit with a strap for talking — a punishment she knew she would have to endure one day.

A few years later, Bernard said, she saw her brother — with whom she wasn’t allowed to speak because girls and boys were separated — being beaten by a staff member. Bernard said she jumped on the man to defend her brother and was slapped with a strap in return.

“Those things were really hard for me as a child,” Bernard said.

Although these memories aren’t easy to talk about, Bernard said she wants to make sure that the ordeal experienced by Indigenous children at the schools is never forgotten. Designating her old school as a national historic site will help, she added.

“My vision is that it will be a place where people can go, read the plaque, go to the place where the school once stood and to start that conversation of the history of the residential school and look for more information,” she said.

Commemoration will also help remind Canadians that the residential schools existed, she said. Right now, there’s nothing at the site of the former Shubenacadie Residential School to indicate what it used to be. A plastics factory now stands in its place.

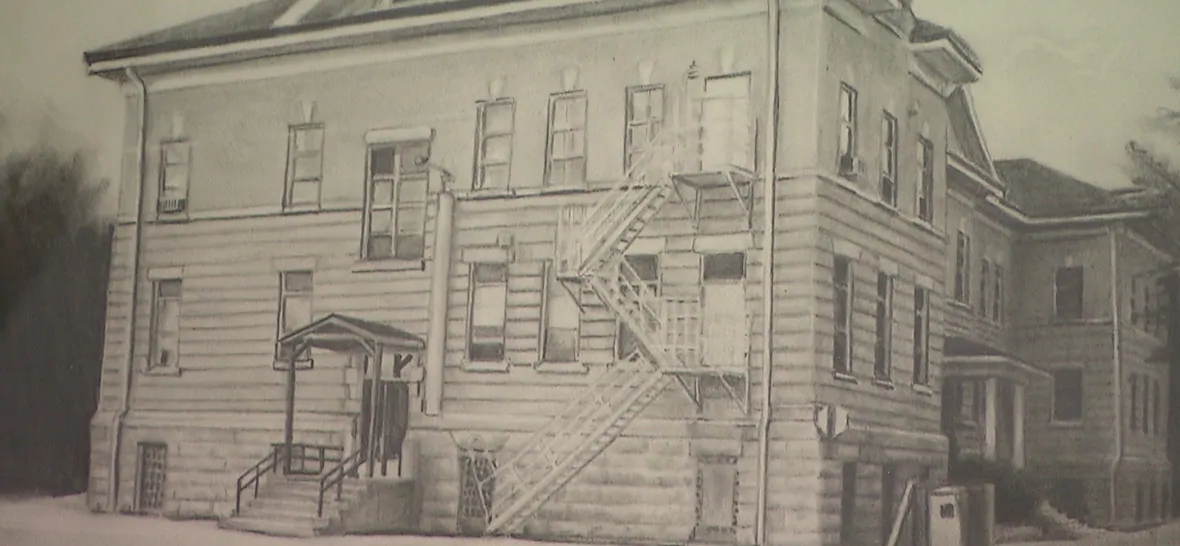

The building that housed the former Portage La Prairie Residential School in Manitoba is still standing.

Long Plain First Nation acquired it in 1981. Once it’s declared a national historic site, said Chief Dennis Meeches, the First Nation hopes to turn the building into a residential school museum, library and memorial garden.

“There will come a day when all of our survivors will have gone on,” Meeches said. “A national historic site — that designation is forever.”

Meeches’ mother, aunts, uncles and grandparents all went to the school.

He said his mom tried to run away with two friends when they were in their early teens; they were caught and school staff shaved their heads as punishment.

“We hear people who would rather see these buildings torn down or demolished, but many of us also feel like we need to preserve that history,” Meeches said. “We can’t erase that history.”

At least 150,000 First Nation, Inuit and Métis children were separated from their families and communities and forced to attend residential schools from the late 1800s until the last school closed in the 1990s.

Most of the schools were administered and funded by the federal government, but were operated by churches and religious organizations.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) final report said the residential school system amounted to a program of “cultural genocide” against Indigenous people in Canada.

Students lost their language, culture and family ties. Many were forcibly removed from their homes to go to the schools, where they faced harsh discipline and abuse.

In 2008, the federal government formally apologized for the residential school system and other government policies of assimilation.

“It’s something that I think many Canadians don’t know as much about as perhaps they should,” Wilkinson said.

The federal government’s move comes five years after the Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommended national commemoration of residential school sites, their history and legacy.

The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation nominated the residential school system for consideration as a national historic event.

Centre director Ry Moran said the recognition covers the entire residential school project — from the decisions made by the political leaders who created the system to the damage done to generations of Indigenous children to efforts by survivors to tell their stories.

Moran said it also offers a chance to celebrate the strength and resilience in the survivor community. He said he expects more communities will nominate their schools for designation as national historic sites.

“It’s an exceptionally important step in our country’s recognition of the harms that it has created within Indigenous communities,” he said.

“The places themselves are but shells of what occurred there. Really, what we are looking to do with all of this work is to honour, remember, acknowledge what it is that those students who attended those schools suffered through and the incredible gift that they have given us, collectively as a country, to better understand ourselves.”

If you’re experiencing trauma, a National Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for former residential school students. You can access information on the website or access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-Hour National Crisis Line: 1-866-925-4419.